Introduction

First of all, what does term "inline" mean?

Generally the inline term is used to instruct the compiler to insert the code of a function into the code of its caller at the point where the actual call is made. Such functions are called "inline functions". The benefit of inlining is that it reduces function-call overhead.

Now, it's easier to guess about inline assembly. It is just a set of assembly instructions written as inline functions. Inline assembly is used for speed, and you ought to believe me that it is frequently used in system programming.

We can mix the assembly statements within C/C++ programs using keyword asm. Inline assembly is important because of its ability to operate and make its output visible on C/C++ variables.

GCC Inline Assembly Syntax

Assembly language appears in two flavors: Intel Style & AT&T style. GNU C compiler i.e. GCC uses AT&T syntax and this is what we would use. Let us look at some of the major differences of this style as against the Intel Style.

If you are wondering how you can use GCC on Windows, you can just download Cygwin from www.cygwin.com.

- Register Naming: Register names are prefixed with

%, so that registers are %eax, %cl etc, instead of just eax, cl. - Ordering of operands: Unlike Intel convention (first operand is destination), the order of operands is source(s) first, and destination last. For example, Intel syntax "

mov eax, edx" will look like "mov %edx, %eax" in AT&T assembly. - Operand Size: In AT&T syntax, the size of memory operands is determined from the last character of the op-code name. The suffix is

b for (8-bit) byte, w for (16-bit) word, and l for (32-bit) long. For example, the correct syntax for the above instruction would have been "movl %edx, %eax". - Immediate Operand: Immediate operands are marked with a

$ prefix, as in "addl $5, %eax", which means add immediate long value 5 to register %eax). - Memory Operands: Missing operand prefix indicates it is a memory-address; hence "

movl $bar, %ebx" puts the address of variable bar into register %ebx, but "movl bar, %ebx" puts the contents of variable bar into register %ebx. - Indexing: Indexing or indirection is done by enclosing the index register or indirection memory cell address in parentheses. For example, "

movl 8(%ebp), %eax" (moves the contents at offset 8 from the cell pointed to by %ebp into register %eax).

For all our code, we would be working on Intel x86 processors. This information is necessary since all instructions may or may not work with other processors.

Basic Inline Code

We can use either of the following formats for basic inline assembly.

asm("assembly code");

or

__asm__ ("assembly code")

Example:

asm("movl %ebx, %eax");

__asm__("movb %ch, (%ebx)")

Just in case we have more than one assembly instruction, use semicolon at the end of each instruction.

Please refer to the example below (available in basic_arithmetic.c in downloads).

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

__asm__ ( "movl $10, %eax;"

"movl $20, %ebx;"

"addl %ebx, %eax;"

)

__asm__ ( "movl $10, %eax;"

"movl $20, %ebx;"

"subl %ebx, %eax;"

)

__asm__ ( "movl $10, %eax;"

"movl $20, %ebx;"

"imull %ebx, %eax;"

)

return 0

}

Compile it using "-g" option of GNU C compiler "gcc" to keep debugging information with the executable and then using GNU Debugger "gdb" to inspect the contents of CPU registers.

Extended Assembly

In extended assembly, we can also specify the operands. It allows us to specify the input registers, output registers and a list of clobbered registers.

asm ( "assembly code"

: output operands

: input operands

: list of clobbered registers

);

If there are no output operands but there are input operands, we must place two consecutive colons surrounding the place where the output operands would go.

It is not mandatory to specify the list of clobbered registers to use, we can leave that to GCC and GCC’s optimization scheme do the needful.

Example (1)

asm ("movl %%eax, %0;" : "=r" ( val ));

In this example, the variable "val" is kept in a register, the value in register eax is copied onto that register, and the value of "val" is updated into the memory from this register.

When the "r" constraint is specified, gcc may keep the variable in any of the available General Purpose Registers. We can also specify the register names directly by using specific register constraints.

The register constraints are as follows :

+---+--------------------+

| r | Register(s) |

+---+--------------------+

| a | %eax, %ax, %al |

| b | %ebx, %bx, %bl |

| c | %ecx, %cx, %cl |

| d | %edx, %dx, %dl |

| S | %esi, %si |

| D | %edi, %di |

+---+--------------------+

Example (2)

int no = 100, val ;

asm ("movl %1, %%ebx;"

"movl %%ebx, %0;"

: "=r" ( val )

: "r" ( no )

: "%ebx"

);

In the above example, "val" is the output operand, referred to by %0 and "no" is the input operand, referred to by %1. "r" is a constraint on the operands, which says to GCC to use any register for storing the operands.

Output operand constraint should have a constraint modifier "=" to specify the output operand in write-only mode. There are two %’s prefixed to the register name, which helps GCC to distinguish between the operands and registers. operands have a single % as prefix.

The clobbered register %ebx after the third colon informs the GCC that the value of %ebx is to be modified inside "asm", so GCC won't use this register to store any other value.

Example (3)

int arg1, arg2, add ;

__asm__ ( "addl %%ebx, %%eax;"

: "=a" (add)

: "a" (arg1), "b" (arg2) )

Here "add" is the output operand referred to by register eax. And arg1 and arg2 are input operands referred to by registers eax and ebx respectively.

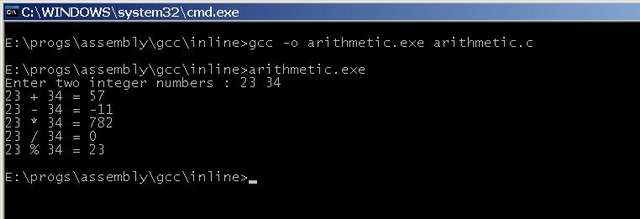

Let us see a complete example using extended inline assembly statements. It performs simple arithmetic operations on integer operands and displays the result (available as arithmetic.c in downloads).

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

int arg1, arg2, add, sub, mul, quo, rem ;

printf( "Enter two integer numbers : " );

scanf( "%d%d", &arg1, &arg2 );

__asm__ ( "addl %%ebx, %%eax;" : "=a" (add) : "a" (arg1) , "b" (arg2) )

__asm__ ( "subl %%ebx, %%eax;" : "=a" (sub) : "a" (arg1) , "b" (arg2) )

__asm__ ( "imull %%ebx, %%eax;" : "=a" (mul) : "a" (arg1) , "b" (arg2) )

__asm__ ( "movl $0x0, %%edx;"

"movl %2, %%eax;"

"movl %3, %%ebx;"

"idivl %%ebx;" : "=a" (quo), "=d" (rem) : "g" (arg1), "g" (arg2) )

printf( "%d + %d = %d\n", arg1, arg2, add )

printf( "%d - %d = %d\n", arg1, arg2, sub )

printf( "%d * %d = %d\n", arg1, arg2, mul )

printf( "%d / %d = %d\n", arg1, arg2, quo )

printf( "%d %% %d = %d\n", arg1, arg2, rem )

return 0

}

Volatile

If our assembly statement must execute where we put it, (i.e. must not be moved out of a loop as an optimization), put the keyword "volatile" or "__volatile__" after "asm" or "__asm__" and before the ()s.

asm volatile ( "...;"

"...;" : ... );

or

__asm__ __volatile__ ( "...;"

"...;" : ... )

Refer to the following example, which computes the Greatest Common Divisor using well known Euclid's Algorithm ( honoured as first algorithm).

#include <stdio.h>

int gcd( int a, int b ) {

int result ;

__asm__ __volatile__ ( "movl %1, %%eax;"

"movl %2, %%ebx;"

"CONTD: cmpl $0, %%ebx;"

"je DONE;"

"xorl %%edx, %%edx;"

"idivl %%ebx;"

"movl %%ebx, %%eax;"

"movl %%edx, %%ebx;"

"jmp CONTD;"

"DONE: movl %%eax, %0;" : "=g" (result) : "g" (a), "g" (b)

)

return result

}

int main() {

int first, second ;

printf( "Enter two integers : " ) ;

scanf( "%d%d", &first, &second );

printf( "GCD of %d & %d is %d\n", first, second, gcd(first, second) ) ;

return 0 ;

}

Here are some more examples which use FPU (Floating Point Unit) Instruction Set.

An example program to perform simple floating point arithmetic:

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

float arg1, arg2, add, sub, mul, div ;

printf( "Enter two numbers : " );

scanf( "%f%f", &arg1, &arg2 );

__asm__ ( "fld %1;"

"fld %2;"

"fadd;"

"fstp %0;" : "=g" (add) : "g" (arg1), "g" (arg2) )

__asm__ ( "fld %2;"

"fld %1;"

"fsub;"

"fstp %0;" : "=g" (sub) : "g" (arg1), "g" (arg2) )

__asm__ ( "fld %1;"

"fld %2;"

"fmul;"

"fstp %0;" : "=g" (mul) : "g" (arg1), "g" (arg2) )

__asm__ ( "fld %2;"

"fld %1;"

"fdiv;"

"fstp %0;" : "=g" (div) : "g" (arg1), "g" (arg2) )

printf( "%f + %f = %f\n", arg1, arg2, add )

printf( "%f - %f = %f\n", arg1, arg2, sub )

printf( "%f * %f = %f\n", arg1, arg2, mul )

printf( "%f / %f = %f\n", arg1, arg2, div )

return 0

}

Example program to compute trigonometrical functions like sin and cos:

#include <stdio.h>

float sinx( float degree ) {

float result, two_right_angles = 180.0f ;

__asm__ __volatile__ ( "fld %1;"

"fld %2;"

"fldpi;"

"fmul;"

"fdiv;"

"fsin;"

"fstp %0;" : "=g" (result) :

"g"(two_right_angles), "g" (degree)

)

return result

}

float cosx( float degree ) {

float result, two_right_angles = 180.0f, radians ;

__asm__ __volatile__ ( "fld %1;"

"fld %2;"

"fldpi;"

"fmul;"

"fdiv;"

"fstp %0;" : "=g" (radians) :

"g"(two_right_angles), "g" (degree)

)

__asm__ __volatile__ ( "fld %1;"

"fcos;"

"fstp %0;" : "=g" (result) : "g" (radians)

)

return result

}

float square_root( float val ) {

float result ;

__asm__ __volatile__ ( "fld %1;"

"fsqrt;"

"fstp %0;" : "=g" (result) : "g" (val)

)

return result

}

int main() {

float theta ;

printf( "Enter theta in degrees : " ) ;

scanf( "%f", &theta ) ;

printf( "sinx(%f) = %f\n", theta, sinx( theta ) );

printf( "cosx(%f) = %f\n", theta, cosx( theta ) );

printf( "square_root(%f) = %f\n", theta, square_root( theta ) ) ;

return 0 ;

}

Summary

GCC uses AT&T style assembly statements and we can use asm keyword to specify basic as well as extended assembly instructions. Using inline assembly can reduce the number of instructions required to be executed by the processor. In our example of GCD, if we implement using inline assembly, the number of instructions required for calculation would be much less as compared to normal C code using Euclid's Algorithm.

You can also visit Eduzine© - electronic technology magazine of EduJini, the company that I work with.

History

- 15th October, 2006: Initial post

This member has not yet provided a Biography. Assume it's interesting and varied, and probably something to do with programming.

General

General  News

News  Suggestion

Suggestion  Question

Question  Bug

Bug  Answer

Answer  Joke

Joke  Praise

Praise  Rant

Rant  Admin

Admin

)

)